I recently had the great fortune to be interviewed by Jay Ferguson, creator of the Emmy award-winning transmedia experience Guidestones. In these three videos, we gab about the future of the craft, being a creator in the transmedia space, and the blossoming business opportunities for transmedia programming. Enjoy!

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 33 -- The Lizzie Bennet Diaries /

This week’s guests are the creative team behind The Lizzie Bennet Diaries: Bernie Su, Margaret Dunlap, Jenni Powell, and Jay Bushman.

Links mentioned in this episode:

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 32 -- Henry Jenkins /

Professor Henry Jenkins is our guest in this episode! He and J.C. sit down and talk about our current culture of shareable, spreadable media in this epic podcast. Also, ARGNet’s Michael Andersen stops by to update us on the latest goings-on in the ARG world, and Steve and J.C. talk Blade Runner, Survivor and their latest console game addictions.

Note: In our conversation with Michael Andersen, John Green was mistakenly identified as a co-creator of The Lizzie Bennet Diaries. We intended to reference co-creator Hank Green instead. We apologize for the oversight.

Links mentioned in this episode:

- Henry Jenkins’ website

- Spreadable Media website

- Transmedia: Hollywood website

- You Didn’t Make the Harlem Shake Go Viral – Corporations Did

- ARGNet

- The Lizzie Bennet Diaries

- Lizzie Bennet Kickstarter

- Arkham City

- Bioshock

- Bioshock Infinite

- Sim City

- Alpha Protocol

- God of War: Ascension

- Cinespia

- Blade Runner

- The Million Dollar Theater

- Wise Guys Events

- Myles Nye’s website

- Myles’ Latest Survivor Challenge

My new favorite thing. /

J.C. joins forces with Protagonist Labs /

Cool things are afoot over at Protagonist Labs. Damned cool things.

When the brilliant team at the new company — led by a duo of entrepreneurs and technologists named Stephen Hood and Josh Whiting — recently contacted me and tipped me to a remarkable new product they were developing, I had a bona fide lean in moment. I think my eyes went a little wide. I know I grinned like a kid.

It's supercool stuff. It's also super-secret stuff for now, but dude. Dude. It's supercool.

Stephen and Josh follow and enjoy my prose fiction and transmedia work, and felt my creative perspective and unique storytelling skillset might help them shape this innovative product. I can't tell you what it is, but I can tell you it's unlike anything I've ever worked on ... and it's right up my alley. I couldn't say no.

And so, it's my absolute honor to announce that I'm an advisor for the company. This is a trailblazing thing we're putting together, something I believe will absolutely be worth your time and attention ... especially if you like the kind of stories I tell, and how they're told.

Other creative people, such as the supremely gifted writer and game designer Will Hindmarch, are also advising Protagonist Labs. I'm flattered to be in such awesome company, and advising such an awesome company. Stephen and Josh are crafting something remarkable, and I'm thrilled to be a part of it.

And be sure to check out Protagonist Labs and its founders (and try to guess what they're up to!) by visiting the company's site, or following the company on Twitter.

—J.C.

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 31 -- Jeff Gomez /

In this episode, we welcome Jeff Gomez (Starlight Runner), as J.C. talks with him about his unique brand of world-building in the transmedia space. Also, Steve launches his new project, Hey! Look Up!

Links mentioned in this episode:

Hello, Daddy. Hello, Mom. I'm your ch-ch-ch-ch... /

Watch your back, shoot straight, conserve ammo, and never, ever cut a deal with a dragon.

—Shadowrunner street proverb

I'm honored and delighted to announce that I'm a contributor to the Shadowrun Returns short story anthology, which will be published later this year by Harebrained Schemes and Catalyst Game Labs.

My story, titled Cherry Bomb, will accompany works from awesome writers (and veteran Shadowrun contributors) such as Michael A. Stackpole, Tom Dowd, Loren L. Coleman, Jason Hardy, Jennifer Brozek and Russell Zimmerman.

I've worked closely with my longtime collaborator — and Shadowrun creator — Jordan Weisman on this story. Fans of my work will recognize some of our past projects, including Personal Effects: Dark Art, Nanovor and the educational transmedia experience Edgar Allan Poe.

I also clocked in time with the anthology's managing editor John Helfers. My objective: To ensure that Cherry Bomb seamlessly and authentically integrated with the existing canon of the badass fantasy-cyberpunk world of Shadowrun ... and intertwined with the narrative seen in Shadowrun Returns, the upcoming video game from Weisman's company Harebrained Schemes.

I've been a fan of Shadowrun since the early 1990s, so this is literally a creative dream come true for me. I fondly recall poring over Shadowrun RPG sourcebooks and playing the Super Nintendo game back in the day. It was a genuine honor to slip into this world once more, this time not just as a consumer, but as a creator. The fact that Cherry Bomb is a canonical prequel to the highly-anticipated Shadowrun Returns game is cool beyond measure.

Last March, Weisman and his team launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund Shadowrun Returns. They had an ambitious fundraising goal of $400,000. Thirty days and more than 36,000 backers later, the campaign earned more than $1.8 million. Shadowrun is a beloved storyworld indeed.

The game — and a package that includes the Shadowrun Returns anthology, and my Cherry Bomb story — is available for pre-order at Harebrained Schemes' website.

If you're unfamiliar with Shadowrun, here's a quick 101, cribbed (and edited) from Wikipedia:

Shadowrun takes place several decades in the future. In 2011, once-mythological beings (such as dragons) appeared on Earth and old forms of magic suddenly re-emerged. Large numbers of humans mutated into orks and trolls, while human children began to be born as elves, dwarves, and even more exotic creatures.

In parallel with these magical developments, the setting's early 21st century features technological and social developments associated with cyberpunk science fiction. Megacorporations control the lives of their employees and command their own armies. Technology advances make cyberware (mechanical replacement body parts) and bioware (augmented vat-grown body parts implanted in place of natural organs) common.

When conflicts arise, corporations and other organizations subcontract their dirty work to specialists, who then perform "shadowruns." The most skilled of these specialists, called shadowrunners, have earned a reputation for getting the job done. They have developed a knack for staying alive, and prospering, in the dangerous world of Shadowrun.

By all appearances, the Shadowrun Returns video game (set in the 2050 era of the storyworld) has turned into something righteously cool. I've gabbed with Jordan a few times over the past year, as the game has been developed. He and his team are busting their humps to make this game something that lives up to player expectations — expectations that have been 20+ years in the making!

It's an unenviable task, but check out this "first look" Alpha gameplay footage, hosted by Weisman and Mitch Gitelman, Harebrained Schemes' studio manager and co-founder. I think they've nailed it.

Like I said, you can pre-order your copy of Shadowrun Returns today at the company's website. If you're keen to snag my story Cherry Bomb, be sure to pre-order the package that includes the illustrated anthology.

Oh, I guess you want to know what Cherry Bomb is about. It explores if two people from wildly different worlds can fall in love while working in an ultra-polluted, ultraviolent superslum. It's also about gunfire. And blood. And pathological lying.

But it's mostly about love. I promise.

—J.C.

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 30 -- Listener Q&A /

It’s listener mail time! Steve and J.C. answer your questions, sent in via all the social networks and wonders of technology. Also: We talk about J.C.’s inability to pronounce tall pale British actors’ names correctly.

Links mentioned in this episode:

- Why I’m quitting Facebook by Douglas Rushkoff (CNN)

- 003: The BBC’s Sherlock, Transmedia From Inception

- 010: In the History-Makin’ Business

- 009: “Transmedia is a Lie”

- 014: The Definition of Interactivity

- 005: Risks of Creative Versatility, Joys of Street-Level Storytelling

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 29 -- Mike Selinker /

Our guest is Mike Selinker (Lone Shark Games). Mike, whose puzzles appear regularly in GAMES magazine, The Chicago Tribune and The New York Times, talks with Steve and J.C. about his time at Wizards of the Coast, building ARGs like the one he did for Universal’s Repo Men, and his new book Maze of Games. Plus, if you pay attention, you just might hear a mysterious message!

Links mentioned in this episode:

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 28 -- Lina Srivastava /

Steve and J.C. spend a little time with Lina Srivastava, as they talk about using transmedia techniques for activism, raising awareness and change. Also, ARGNet’s Michael J Andersen stops by to let us know what’s happening in the ARG world.

Links mentioned in this episode:

- AUTHENTIC IN ALL CAPS crowdfunding campaign

- The Walking Dead from Telltale Games

- Lina Srivastava’s site

- Lina Srivastava’s LinkedIn

- Lina Srivastava’s Twitter

- ARGNet

- MIT Mystery Hunt

- The Lost Children

- The Maze of Games Kickstarter campaign

People Are Wonderful. /

Blood On My Hands: My Failure & Redemption in "Mass Effect" /

Warning: This post is packed with plot spoilers for the Mass Effect trilogy.

I completed the Mass Effect video game trilogy more than a week ago, and yet a hearty chunk of my mind stubbornly remains back there, on those many worlds, considering the many choices I made. The mistakes I made.

Looking back now, I realize when I became smitten by the series. It was a scene in the first game. It took less than two minutes to unfold, and ended with a thunderclap. Though I wouldn't realize it until much later, this moment made a profound impact on how I played the rest of the game, and its two sequels. Get your head around that: Dozens of hours of play, all affected by 90 seconds.

Sometimes, that's all it takes. Kinda like real life.

A LEGACY OF PAIN

I've already shared a bit about how I played my Commander Shepard during the series. The Greatest Hits recap: My Shepard was a surly soldier who didn't truck with bullshit. She was an orphan born on Earth, a former criminal who did absolutely everything it took to achieve her mission objectives. She didn't like aliens much, mostly because they didn't like her. She trusted no one. She was merciless.

As the scope of Mass Effect's story widened, my Shepard dropped the attitude about aliens. This was mostly brought on by her collaborations with several aliens during the story, all of whom were brilliantly realized characters, and righteous badasses.

There was another influencing factor, however. Ashley Williams, a member of Shepard's crew, was xenophobic. Her deep mistrust hailed from family history and military experience. Ashley's reasons may have been legit, but I soon realized it didn't matter. See, you start to wonder about your own biases when bigots evangelize their closed-minded hate. Ashley's behavior soon changed Shepard's, and for the better.

My favorite alien crew member was Wrex, the only character in Mass Effect 1 whose surly sass could keep pace with my Shepard's. The krogan bounty hunter loved to fight, but he wasn't a stupid brute. He was heartbroken about how his species remained on the brink of extinction due to the "genophage," a biological weapon deployed 1,000 years ago by two colluding alien species. Their goal had been to control the krogan population, and it had worked. The krogan didn't have a say in the matter.

Wrex and Shepard

Truthfully, the krogan hadn't fully controlled their fate for some time. The species was technologically "uplifted" by other aliens 1,000 years before the genophage to be used as a willing army against the aggressive rachni, a conquering insect-like race.

This technological empowerment created big problems. After the Rachni Wars, the krogan aggressively expanded their borders. Left unchecked, they — and the war they inevitably brought with them — might have dominated the galaxy. The genophage "solution" was released, and everything changed.

Wrex was right to be heartbroken about the genophage. For 1,000 years, only one in every 1,000 krogan survived birth. Fatalistic thinking had plagued the species ever since; its males marched off to war against opposing krogan clans, or they worked as mercs. Most came home in body bags, filled with bullets. The species was dying.

Wrex wanted more for his people. He hoped the krogan might one day be cured. I did too. I reckoned a thousand years of pain, and god knew how many billions of dead babies, was penance enough. I didn't believe anyone had the right to make such a devastating and species-changing decision as the genophage.

A FRIEND LOST

Which brings us to the planet Virmire, where 90 seconds of dialogue changed how I played the Mass Effect trilogy.

Folks who've played Mass Effect 1 probably recall that Saren, a rogue Spectre brainwashed by the villainous Reapers, was up to no good at Virmire. There, he'd built a facility that was successfully breeding a krogan army. Saren had concocted a cure for the genophage. In order to thwart Saren's galaxy-threatening plan, it became clear that the base — and in the process, the genophage cure — would be destroyed.

For 90 seconds, my Shepard and Wrex argued about this. Wrex demanded the squad retrieve the cure. I tried to explain that Shepard was sympathetic, but it couldn't be done. Wrex countered that the salvation for his people was within reach. The cure would not be destroyed.

As a player, this was a very long 90 seconds. I pined for another game option to agree with Wrex and hunt down the cure, but none existed. Wrex became furious. He pointed a gun at my Shepard's face. I gazed at the conversation options, helpless and horrified as I spotted several choices that were "grayed out," inaccessible — I hadn't acquired enough in-game experience to intimidate or persuade Wrex. All I could do was try to talk him down.

And that's when crew member Ashley Williams shot Wrex in the back. She then plugged him three more times as he gasped in the sand. Wrex was dead. I was aghast. I'd been powerless to stop any of it.

And in that moment — a miraculous moment that I intellectually understand is a complex illusion; a fabrication of polygons, textures and dialogue written by someone like me; make-believe, man — I hated Ashley. I experienced genuine hatred. I seethed at her disregard for Shepard's authority, at the betrayal, and at the bigotry that probably helped her pull the trigger.

Ashley Williams

Not long later, when I had to order a crew member to his/her death during a final all-or-nothing assault on Saren's Virmire base, I chose Ashley. I did this without hesitation. I chose her because of what she'd done, and the pain she'd brought me. My heart had gone cold, and cruel, and I didn't care.

And that's when I realized I was smitten by the series. I'd made a decision based not on some elaborate meta-game analysis of risks and rewards, but one based solely on emotion. More remarkably, I felt no remorse when she died.

That was the end of that.

But it wasn't. I didn't know it, but I was still haunted by Wrex's death. I'd be haunted well into Mass Effect 3.

A FAMILY FORGED

In meta-game woulda-shoulda-coulda conversations that so many gamers have with themselves, Wrex's death represents a spectacular failure, my punishment for rushing through the game, ignoring experience-boosting side quests. Thankfully, my brain doesn't work this way. I don't enjoy fussing at myself, or trying to outsmart the game. I play games the way I want, and roll with whatever bruises they give me. Losing Wrex was a helluva shiner, but by the end of Mass Effect 1, my Shepard had put the bloody matter behind her, rose to the challenge and righteously kicked some Reaper ass.

Mass Effect 2's prologue is the best video game beginning I've ever played. Not only does the destruction of Shepard's beloved spaceship Normandy serve as an iconic, disruptive, the-rules-just-changed-you're-in-the-shit-now moment — the subsequent death and resurrection of Shepard effortlessly reboots the character, her abilities and her in-game experience, creating a perfect starting point for both veteran and new players. A clean slate for all, completely justified by story. So damned clever.

But the slate wasn't completely clean. Mass Effect 2 is about the ruin and reassembly of family. In it, Shepard is tasked with saying farewell to the Alliance — the institution that forged her (or him) into a warrior-leader — and must work with the dangerous shadow organization Cerberus. Here, Shepard must reforge relationships with allies two years gone, and make many new ones. The objective: To build a Dirty Dozen-inspired "suicide squad" tasked with taking down the Collectors, an alien race working for the Reapers.

Nearly all of the crew members Shepard recruits are outsiders — untethered humans and aliens who are either family-less, or have deep familial issues they wish to repair. To ensure the loyalty of her crew, Shepard must help these misfits. Genetically-engineered human Miranda Lawson wishes to protect her kid sister (who is in fact a clone of Miranda herself) from her tyrannical father. Masked quarian Tali'Zorah and human Jacob Taylor discover dark secrets about their fathers, servicemen who were highly regarded. Asari knight-errant Samara must confront and murder her daughter, who has become a serial killer.

Jack

In contrast, Jack, a remorseless criminal and killer, had no family. She had been abducted as a child by Cerberus (the very organization with whom Shepard is now in league), and was confined at a research facility that tested her remarkable telekinetic powers for years. She eventually escaped, murdered anyone in her way, and lived a thug's life until she was arrested and tossed into a cryogenic prison. Shepard springs her from jail in Mass Effect 2, and helps her destroy the research facility that broke her mind and spirit all those years ago.

Jack was damaged goods, bruised to the bone. She resented authority, seemed pathologically selfish, was unreservedly surly ... and was hella great in a fight. She and Shepard got on just fine. I reckoned Jack would ditch her bad attitude after I helped her say goodbye to her painful past. But she didn't. Because saying goodbye is never that easy.

Indeed, it was the appearance of another krogan in Mass Effect 2 that reminded me of the blood on my own hands, and how I'd failed Wrex and the krogan species in the first game. The creature named Grunt was a young krogan, grown in a vat, genetically engineered to be "pure" — a super soldier, a relentless killing machine.

Grunt

He was sleeping in a stasis chamber when my Shepard found him. Shepard had a clear choice in how to proceed: Leave the chamber closed (and keep the sleeping apex predator inside), or open the chamber and risk the safety of, well, frickin' everybody.

This next bit is important to understand. I didn't choose to open the tank because I wanted a new squadmate, or a better game ending, or other perks meta-gamers savvily strategize about. I chose to open the tank because I wanted to make things right. I knew Grunt couldn't replace Wrex — and indeed, I didn't take a shine to him the way I did my pal from Mass Effect 1 — but I reasoned there was a karmic debt that needed to be paid. My bad decisions had contributed to the taking of a krogan life, and here I was, bringing a new one into the world.

A quick sidebar: This karmic subtext is an invention all my own, of course. Internalized, deeply personal, player-created narratives like this one are perhaps the thing I love most about the Mass Effect games (and other superb choice-driven games such as The Walking Dead). This guilt I had ... the desire to right wrongs from games past ... it was all created in my mind, a byproduct of my emotional investment in the storyworld, characters and plot. Great writing does this. Great voice performances does this. Great character animation does this.

One of my most memorable internalized narrative beats in the series occurred during the endgame of Mass Effect 2. In the midst of invading the Collector base, Shepard's crew was besieged by swarms of Seekers, insect-like things that sting and paralyze their prey. I had to choose a squaddie with biotic (telekinetic) powers who could create a forcefield bubble to protect the squad against the swarm.

Jack, shining bright

Samara, the super-powerful asari knight-errant, was the clear choice. She was nearly 1,000 years old, and a disciplined, even-tempered telekinectic. But I wanted unpredictable Jack — she of the ruined past, she who was pathologically selfish — to have a bona-fide Hero moment, a moment where she was given the greatest responsibility of all. I had no idea if she'd come through; I just knew that after a lifetime of living in the dark, she needed a moment to shine bright. She did.

But back to the middle of Mass Effect 2 and Grunt, and the stasis tank. My Shepard opened the tank, and a great story arc began. When it came to Grunt and the krogan, it wouldn't be my last emotionally-motivated decision. In Mass Effect 2, I ordered the fast-talking salarian doctor Mordin to save some data regarding a genophage cure that had been obtained through terrible, unethical medical research. It was unlikely it could ever lead to a cure.

It didn't matter, not to me. I was trying to make things right, see.

A SECOND CHANCE

In Mass Effect 3, curing the genophage became a priority for the krogan. Considering my Shepard's arc through the series (and my personal feelings about Wrex, the genophage and the unjust punishment of the krogan 1,000 years ago), my character did everything she could to broker an alliance between the genophage's creators and the krogan.

My Shepard birddogged a cure, using the unethical research data saved from Mass Effect 2. She allied herself with the species at every turn, especially so with the female krogan Eve. As a player, I knew that the krogan, if cured, might hunger to conquer regions of the galaxy as they had generations ago. But I hoped they would instead help maintain the galactic unity Shepard was building during this stage of the war.

Mordin

This was a big risk, considering the subversive, revenge-minded talk hailing from Wreave, the krogan clan leader with whom I liaised. Ultimately, I had faith that trust and mercy were the best-possible options.

Trust and mercy. My character had come a long way from being the human-centric, ruthless grunt of Mass Effect 1.

There were moments when I could have sabotaged the genophage cure. I didn't. I saw it through. My Shepard lost a dear ally in the process — surely another moment of karmic balance, for victory and closure cannot come without sacrifice.

And as I watched the snowflakes of genophage cure drift down from Tuchanka's dusty sky, I finally let Wrex go. I finally put that bloody business to bed. Those terrible 90 seconds, all those dozens of hours ago.

A FINAL CHOICE

I can't say for certain if Wrex's death, and my relentless, games-long pursuit to right that particular wrong, influenced my final decision in Mass Effect 3 in a meaningful way, but it certainly informed it.

Players of the third game recall the ending's three primary choices:

- Destroy the Reapers, which would also kill all synthetic life forms throughout the galaxy, such as the geth and EDI. Even with the Reapers gone, interstellar peace would not guaranteed. Synthetics and organics might war once more. The krogan could rise up again.

- Control the Reapers, which would kill Shepard, but inject her mind into theirs, ensuring the elimination of the Reaper threat. Even with the Reapers no longer wrecking the galaxy, interstellar peace would not guaranteed. The galactic unity I'd helped create could easily unravel.

- Initiate "Synthesis," in which organic and synthetic life forms would integrate on the cellular level. This would render the Reapers' objective — to prevent organics from extinction, due to an inevitable organic/synthetic war — as obsolete. Due to this galaxy-wide "uplift" in evolution, interstellar peace would be guaranteed.

Shepard's mission, from the beginning of Mass Effect series, was to destroy the Reapers. Considering the galaxy-wide horrors (or meticulously-planned control, depending on your perspective) the Reapers committed every 50,000 years, I was on board with these orders. Kill the fuckers. Kill them all.

And yet at that moment, as my Shepard stood in the heart of the Crucible, panting and bleeding out, my mind reeled from the responsibility and the impossible stakes.

Should I sacrifice millions of innocent synthetic life forms such as the geth for a greater good — the destruction of the Reapers? Trillions of lives would be saved. But I considered the genophage and the unspeakable genocide it wrought for a thousand years, a decision the krogan did not make for themselves. Did I have the right to kill the geth, just as Ashley Williams had killed Wrex on Virmire?

Alternately, should I guarantee a lasting galaxy-wide peace by choosing Synthesis? In one swoop, my decision could end the Reaper threat, and harmonize all sentient life in a way never before seen — a genuine leap forward in evolution. But I considered the "uplifting" of the krogan 2,000 years ago. Did I have the right to make such a sweeping decision for all species ever ... a decision with no take-backs? The krogan hadn't been ready back then. Would the rest of us be now?

And then my mind turned to the genophage cure, and how I'd gone to incredible lengths to ensure its successful creation and release. I had done so because it was the right thing to do. It was just. The decision had not been without risk; the cured krogan might declare vengeance on the galaxy some day, and they'd be within their right to do so.

But I had had faith back then — faith that trust and mercy were the best-possible options. And that was where my mind settled, here, now, in the heart of the Citadel. I had faith it would work out.

My Shepard staggered to the panel that would sacrifice her life, and activate her consciousness' control over the Reapers. Trust and mercy — the two qualities my Shepard didn't have at the beginning of Mass Effect 1 — would be what she shared now. Trust in the galaxy to remain united; mercy for the Reapers.

The ending was wonderful.

A REMARKABLE EXPERIENCE

Now that the story is over, I regard the Mass Effect games with the same reverence I have for such other brilliant science-fiction stories as The Matrix and Vernor Vinge's novel A Deepness In the Sky — I wish I could completely forget them, so I could experience them again for the first time.

For me, the trilogy represents a miraculous thing. It is an experience that one does not control, but influences; a narrative that celebrates personal choice, but wisely — and rightfully — keeps its true rudder far from players' hands. And yet, at nearly every beat during the dozens of hours I was in its storyworld, I was thoroughly convinced that every moment of Mass Effect was my own.

I intellectually understand it's all a complex illusion; a fabrication of polygons, textures and dialogue written by someone like me. It's make-believe, man. But it evoked genuine emotion, passion, and creative inspiration and aspiration.

As I said, a hearty chunk of my mind stubbornly remains back there, on those many worlds, considering the many choices I made. The rest of my mind — the part that's here with you now — will marvel at it for months to come, this genuine and awe-inspiring work of art.

Did the Mass Effect series make a similar impact on you? I'd love to hear about it. Share your own Shepard's stories in the comments.

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 27 -- Ryan Omark, Stephen Omark, Dana Shaw & Tom Pike /

We celebrate the Indie-ARG in this episode! Guests Ryan Omark, Steve Omark (We Are Earthborne), Dana Shaw and Tom Pike (The Wall Will Fall) discuss their Alternate Reality Game projects from inception through execution and completion, along with the challenges they faced and lessons they learned.

Links mentioned in this episode:

On My Character's Unwitting Evolution In "Mass Effect" /

My Shepard's arc throughout the space opera Mass Effect video game trilogy is fun and fascinating to think about.

I resolutely played her as a human-centric Renegade in the first two acts of the first Mass Effect game. I reckoned the awful childhood and ruthless career decisions I'd chosen for her "origin story" in this Role Playing Game would've made her filled with piss and vinegar. She mistrusted aliens, resented authority, shot first and asked questions later. But that changed as the stakes in the game increased. Her little mind opened, she rose to the challenge, made more optimistic (Paragon) decisions than cynical (Renegade) ones, fought for a worthy cause, fell in love, the works.

In the opening acts of Mass Effect 2, I played Shepard as an alien-friendly, but no-compromises Renegade. She was rightfully cynical. She was pissed off at the world for what happened to her in that game's opening moments, and was pissed off at who she was working for. Yet again, she softened and became more Paragon as the pressure piled on, and that game's galaxy-spanning threat became increasingly clear.

These days as I make my way through Mass Effect 3, despite the occasional Renegade moment (for I still sometimes shoot and ask questions later), I nearly always play her like the galaxy-uniting Paragon hero she's supposed to be.

Here's the thing that amazes me. This game-by-game transformation isn't a side-effect of deliberate, thoughtful decisions made by me. I haven't wittingly "willed" my character to evolve over time. Shepard's changes have all hailed from my natural reactions to the rich storyworld, the games' plots, and the hard decisions Shepard has had to make. I didn't "choose" to play my Shepard as softer, or more generous, or open-minded as the series progressed — not with any deliberation, anyway. That evolution just happened. Adaptation? Assimilation? I don't have a word for it.

But I genuinely marvel at it, at the impact it's made on me as a player ... and on the impact it's made on my little world-saving Shepard. That's a testament to the authenticity and immersive qualities of the Mass Effect universe, and how the games clearly present their narrative stakes (and the ethical challenges those stakes evoke). Above all else, it's the characters and writing.

I'm certain I've changed as a person while playing these games, though those revelations will come later. But the changes my little Shepard has gone through, all brought on by the story? Those are worthy of awe, admiration and appreciation. And aspiration.

Damning the NRA's "Gun Range" Game /

Video game enthusiasts who criticize the NRA for releasing a "gun range" iOS game (after the NRA recently, and shamefully, blamed video games for inspiring violent behavior) are falling into a trap. The NRA's "gun range" game doesn't fire ammo at living creatures, and — I presume — encourages gun safety and responsible use.

By screaming about the NRA's iOS game and its irony, gamers are actually providing opportunities for the NRA to showcase the disparities between its "responsible" game and the undeniable ultraviolence seen in most other video games.

It's a honeypot, guys. Be critical, but be thoughtful with that criticism.

Podcast: StoryForward, Episode 26 -- Michael Andersen /

Special guest Michael Andersen (ARGNet) joins Steve and J.C. as they look back at the year 2012. Projects, platforms, ARGs and more, you won’t want to miss this year-in-review episode.

Links mentioned in this episode:

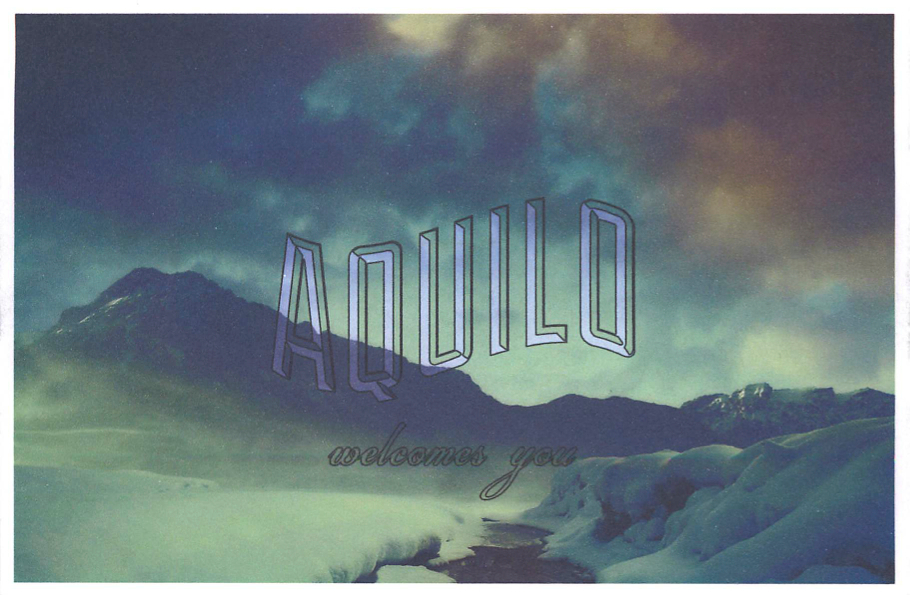

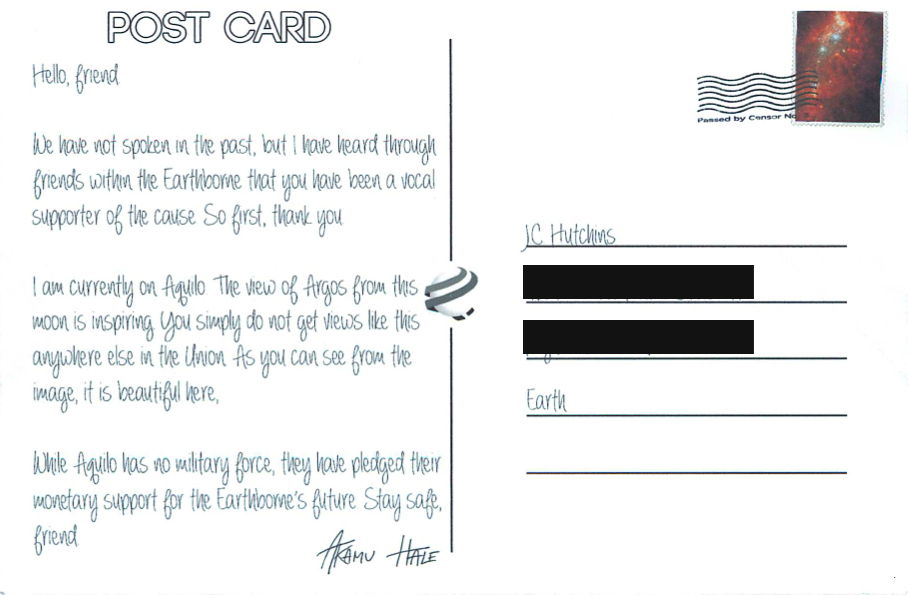

Postcard From The Future /

A few months ago, I received an incredible package in the mail from the Interplanetary Union, an organization based in a location called "New Lyon City," on the planet Centauri. I recorded an unboxing video, and shared the contents of the package with readers.

I learned not long after by Alternate Reality Game players and transmedia enthusiasts that the package was for a fiction project called We Are Earthborne. Remarkable in scope and quality, We Are Earthborne was an independently-produced experience, the brainchild of storytellers Ryan and Stephen Omark. They released the story under their studio, Immersive Fiction. Signs suggest the story concluded mere days ago.

However, I received yet another mailing via the Interplanetary Union yesterday -- this one from the planet Aquilo. It was a postcard from Akumu Hale. Players of the We Are Earthborne game may recognize those names. For newcomers, the postcard represents a brief and curious peek into a remarkable science-fiction world.

Is the postcard a final small rabbit hole for players to pursue, or an epilogue for the experience? I'll leave it to you to decide.

I've scanned the envelope and postcard. Take a look ... and if you're interested in learning more about We Are Earthborne, check out the links below the gallery.

Links:

- We Are Earthborne's site

- We Are Earthborne's Unfiction thread

- Oceanus Wiki

- The We Are Earthborne Codex

- Immersive Fiction

Podcast: Interview with C.C. Chapman, Author of "Amazing Things Will Happen" /

Today, J.C. chats with longtime friend and social media maven & author C.C. Chapman about C.C.'s new nonfiction book, Amazing Things Will Happen.

In many online circles, C.C. is known for his positivity and relentless work ethic. In his new book Amazing Things Will Happen, C.C. explores the tricky subject of self-improvement and embracing change. In this conversation, J.C. and C.C. chat about the book's approach to guiding one's life toward achieving goals and dreams — and not merely settling for current circumstances, as so many of us do.

It's a terrific conversation that goes to some very fun, funny and positive places.

Links mentioned in this episode:

- C.C.'s personal website

- Learn more about Amazing Things Will Happen at the author's website

- Amazing Things Will Happen reviewed in the Washington Post

- The Cleon Foundation

BOOK REVIEW: C.C. Chapman's "Amazing Things Will Happen" /

Hey peeps. I wanted to tip you to a brilliant book written by my friend, the incredible new media creator and marketeer C.C. Chapman.

In many online circles, C.C. is known for his positivity and relentless work ethic. In his new book Amazing Things Will Happen, C.C. explores the tricky subject of self-improvement and embracing change. Where so many other writers fail, C.C. rises above, delivering a masterful and elegantly-written approach to guiding one's life toward achieving goals and dreams (and not merely settling for current circumstances, as so many of us do).

My review of the book is below. But first, a bit more about the book, from the book:

FROM THE BACK COVER

Work hard, be kind, and amazing things will happen. Amazing Things Will Happen offers straightforward advice that can be put into action to improve your life. Through personal anecdotes from the author's life, and interviews of successful individuals across several industries, this book demonstrates how to achieve success, in all aspects of life, through hard work and acts of kindness. Split into five sections, this book details how to begin the self-improvement journey.

MY REVIEW

C.C. Chapman's Amazing Things Will Happen is a remarkable and uplifting — but zero-BS — book designed to help you identify places to improve and succeed in your personal and professional life, and then equip you with the insights to make good on those improvements.

C.C. seems to understand that the greatest problem with self-help books is that they overpromise and often guarantee unrealistic results. This mismanages expectations and leads to disappointment. Amazing Things Will Happen rises above such windbaggery by providing hard-earned, dirt-under-the-fingernails practical lessons and advice. This isn't a road map; it's a toolbox.

Thankfully, the tools C.C. provides are worthy of the reader's attention and action. He provides insights on topics such as: summoning the courage to start a new project (or stage in your life / career) ... how to document and celebrate inspiration when it strikes ... how to deal with fussbudget nay-sayers ... how to acknowledge and embrace risk ... and how to rise above it all to achieve your goals.

It's a brisk read, packed with insights, optimism and gumption. Highly recommended. Get your copy at Amazon today.

—J.C.

Podcast: Interview with Collin Earl & Chris Snelgrove of "The House of Gray" /

Today, J.C. chats with authors and entrepreneurs Collin Earl and Chris Snelgrove. These two ultracreatives are the brilliant minds behind The House Of Gray audio and serialized ebook experience, and the YA series Harmonics.

In this conversation, Collin and Chris share this history and inspiration for The House of Gray, and how it made the fascinating shift from podcast novel to serialized ebook. They also discuss why they embraced the fascinating (and ultimately savvy and profitable) approach to selling the story as serialzed ebooks.

J.C. also asks Collin and Chris about their affordable turnkey ebook and audiobook production company DarkFire, which J.C. uses to format and release his 7th Son ebooks.

It's a terrific chat with two incredible storytellers. Enjoy!

Links mentioned in this episode: